As South Africa celebrates the tenth anniversary of its democracy, several changes have occurred during the past decade which suggest that our democracy has matured rather rapidly. Nowhere is this more apparent than in South Africa’s financial services sector. Yet, despite legislation to ensure compliance with international banking standards, will the South African financial services sector be able to counter various identified threats without using specialist security management consultancies?

Since 1996, the South African Reserve Bank has been in negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the United States Federal Reserve Bank and many European financial institutions to ensure that South Africa can compete on the international stage with a sophisticated and stable money market. To comply with international banking standards, South Africa has promulgated various laws, including:

* Prevention of Organised Crime Act (1996).

* Proceeds of Crime Act (1997).

* Money Laundering Control Act (2000).

* Financial Intelligence Centre Act (2003).

All these laws have been designed to make South Africa compliant with anti-money laundering legislation and to assist with the tracking and tracing of money world-wide. Unfortunately, the effectiveness of these laws have yet to be tested. Meanwhile, the threats of money laundering and terrorist financing remain unchallenged and more stringent methods are required.

Defining money laundering

To understand the need for anti-money laundering legislation, a definition of the term is required. The belief that the Chicago Mob of the 1930s was the first to 'launder' its cash through laundromats is a myth. In fact, the term was first used in connection with the 1973 Watergate scandal during President Nixon's administration. Money laundering is the means by which the illegitimate flow of funds is processed in such a way as to appear to be a legitimate source of income. As such, money laundering has been used by crooks, organised crime, terrorists and even governments to prevent law enforcement agencies from identifying assets or proving that such assets were the proceeds of criminal activities.

Money laundering concerns hiding the proceeds of criminal or illegitimate activity. Admittedly, when the CIA moved money via the BCCI bank it was 'facilitating the national interest' but when the Mafia or Libyans did it, it was called money laundering. Typically, hundreds of billions of dollars are laundered by the global narcotics trade each year because its customers often pay for their drugs in cash. However, bank robbers, embezzlers, tax evaders, corrupt public servants and politicians also need to ensure that their source of income appears legal. To do this, they need to launder their cash in a way that does not attract the attention of law enforcement or tax agencies.

The rules have changed

In the first instance, the illicit money must be physically placed into the financial system. Whilst many individuals are happy to keep their cash under a mattress or in a tin box, this money can only be used in a cash economy to pay for goods or services. When such cash sums total millions, or in some cases billions, of dollars the sheer volume of cash proves that there is no mattress or tin box big enough. After all, a million dollars in cash weighs more than 20 kilograms and fills a couple of briefcases. Therefore, the money has to be deposited with the financial institutions without arousing any suspicion. Before any laws were passed, the cash was bundled together and deposited into the nearest branch by the drugs dealer or trafficker. Imagine walking into a BMW car dealer and paying cash for a 7 Series. The car salesman would take your money and deposit it into the bank. The bank would know the car dealer's business and expect him to report any suspicions of money laundering. These rules were quickly changed.

Smurfing?

The United States was the first country to recognise the need to control money laundering by drug smugglers and dealers. However, to bypass legislation that required banks to report cash deposits of US$10 000 or above, the drug dealers invented 'smurfing'. Individuals were given cash amounts of under US$10 000 and advised of specific deposit taking banks in an area. By placing the cash in various accounts at various branches, the drug lords completed the first step towards legitimising the source of their cash.

Once the money has been placed into the financial system, the layering process begins - pushing the money through multiple transactions using a number of countries and a handful of 'brass plate' companies with nominee directors. In this way, the money is routed around the world and it becomes increasingly difficult to establish whether the money was the proceeds of a crime or not. Money launderers can claim that the money paid by one company to another is in respect of services offered, loans or consultancy fees. The more complicated the transactions become after the initial deposits, the more legitimate the flow of funds. Opportunities for layering cash exist with antique dealers, foreign exchange bureaux, finance houses, jewellers and casinos. Not surprisingly, the scale of money laundering is large and the activity prevalent.

Finally, the launderer needs to transfer the money back to a place and in a form so that it can be used to generate more income. The 'washed' funds are then brought back into circulation as clean and taxable income.

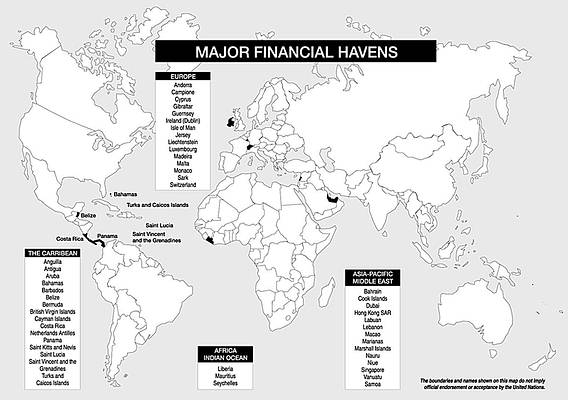

Privacy protects

Offshore financial institutions are useful to money launderers because of their stringent privacy laws. These laws prevent both foreign and local investigators from identifying who really controls a company or a bank account. On the Pacific island of Nauru, its 6000 citizens have over 400 registered banks. Yet, the main financial institutions in London, New York, Paris, Frankfurt and Switzerland also provide similar financial services. In fact, US$1,6 billion stolen by the former Nigerian dictator, Suni Abacha, was found in reputable British and Swiss banks. The brother of the ex-president of Mexico, Raul Salinas, laundered his cash through Citibank; and Oliver North financed the Iran-Contra deals through a Swiss bank. North needed to launder the cash - he had purchased 2000 TOW missiles from the CIA for $12 million and sold them to the Iranians for $30 million. Such substantial profits needed extensive washing before being declared.

Unfortunately, the sheer volume of daily transactions within the multibillion dollar global banking industry makes the task of identifying launderers very difficult for law enforcement and financial institutions. What defines 'suspicious behaviour' and to what extent are banks required to know their customers? Also, the problem of terrorist financing is exacerbated because the money often comes from legitimate sources - such as contributions made to charities, religious schools and foundations.

Parallel banking systems

To prevent the financial institutions from monitoring their funding, organised crime and terrorists in the Middle East and South Asia have relied on an informal money transfer network. This 'parallel banking' system has only added to the difficulty of tracing the money used to finance terrorist activities.

Known as 'Hawallah' in India, 'Hundi' in Pakistan and 'Chop' amongst Chinese immigrants, the centuries old informal banking system does not involve records that can be traced. Tokens in the form of torn playing cards or e-mailed passwords are sent from one country to another instructing a trusted Hawallah broker to deliver a given amount of local currency to its destination. The original sum of money, delivered to the Hawallah broker, never leaves the country of origin. The whole system relies on trust between brokers with any shortfalls being settled on a bi-monthly basis.

The system is often used by people working abroad and sending money home to relatives who may not have a bank account. South Africans have used similar informal banking channels in order to evade exchange control regulations. Unfortunately, terrorist cells also recognised the opportunities and have used the system to divert funds for operational purposes. In the early 1990s, the British police arrested a consortium of six Hawallah brokers who operated between London and two Indian regions - the Punjab and Cashmere. Both Indian regions were centres for rebel movements. The six brokers admitted to laundering in excess of US$80 million in one year. Since 9/11, the number of Hawallah brokers who have been identified and arrested has exceeded 220, excluding those who have been assassinated by Special Forces or anti-terrorist agencies. Despite these successes, the parallel banking system will continue to operate as it has done for the centuries before the modern banking system was born.

Suspicious transaction reports

Suspicious transaction reports (STRs) are the main means of identifying potential money laundering. Some banks are less than diligent about filing them and if they are filed, the banking regulators receive far too many to pay much attention. South African banks simply do not have the people or those with enough experience to play Sherlock Holmes to enforce all the 'know your customer' rules and other regulations. Consequently, many South African financial institutions are facing an enormous duty that could prove almost impossible to fulfill. If this news becomes widely known, the country could unwittingly become a money laundering haven.

Financial institutions are responsible for putting in place systems to deter money laundering and to assist with the investigation of suspicious activities by law enforcement agencies. The banks must also set up procedures for verifying the identity of clients and to train its employees in the procedures of recognising and reporting any suspicions of money laundering.

However, given the global scale of money laundering by organised crime and terrorists alike, it is certain that bank costs in the areas of administration, training and storage space will increase exponentially and that financial institutions will have to pass these increased charges onto their customers.

A structured 4-pronged approach?

Meanwhile, how can independent security consultants and specialist investigative firms assist South African financial institutions? Our experience has shown that the proposed four-pronged approach has ably assisted banks and financial institutions. The approach is effective and demonstrates due care and diligence by the financial institutions involved. Our key services will:

* Confirm the identities of prospective customers and validate their identity documents. False passports, fake ID books, identity theft and other tactics are often used by syndicates and tax evaders to open accounts for money laundering purposes. Often such documents are stolen from other African or Middle East countries.

* Establish whether prospective customers are politically exposed, have criminal records or have attracted the interest of law enforcement and national intelligence agencies in their host countries.

* Determine the source of a prospective customer's wealth. In many African countries, the American dollar is the preferred currency of commerce and cash the preferred method of payment. Simply because a prospective customer wants to bank cash, does not mean that the individual is financing a terrorist cell or laundering their money. Without confirming the source of funds, the financial institution could prejudice its customer base.

* Conduct compliance audits to assess whether funds can be laundered through the financial institution. If tellers conspire with money launderers and STRs are incorrectly filed, then the legislated reporting mechanisms will be breached. As such, the financial institution could face heavy financial penalties and the loss of its trading license.

As the anti-money laundering legislation becomes more onerous and South African financial institutions are forced to comply with ever-stringent legislation, there is a growing need for the expertise of security management professionals. Only by identifying and prosecuting known offenders, can the banks ensure that their costs of complying with legislation is money well invested and will not prejudice the bank's own interests. The alternative is to see the anti-money laundering legislation promulgated but the financial institutions failing to take proper action against suspected or actual offenders. If this happens and South Africa becomes a money laundering haven, the future integrity of our banking system will be in jeopardy.

For more information contact Benedict N. Weaver, Zero Foundation, 021 712 3024, [email protected], www.zerofoundation.com

© Technews Publishing (Pty) Ltd. | All Rights Reserved.