Private security has a longer history than the official public police service. The idea of delegating the responsibility to safeguard a property to hired personnel started during feudal times. There was no public police service that could be contacted when people needed help and assistance.

Public policing agencies are a recent innovation. It was only in the last 300 years that law enforcement agencies, charged with protecting the property and safety of citizens in a country, have become the norm. According to Maggio (2009: 13-15), the first police force was started by the French government of King Louis XIV in 1667. In 1829 England’s Home Secretary Sir Robert Peel introduced a bill in parliament, which proposed a return to the Anglo-Saxon principle of individual community responsibility for the preservation of safety and security in a given community through prevention. The bill also proposed that London, in particular, should have a body of civilians appointed and paid by the local community to serve as full-time police officers. This Anglo-Saxon period, whereby every able person was a police official, is reflected in Peel’s contention that the public was the police and the police was the public.

After World War II, security became important in times of social and economic revival when public security services were not able to accord the degree of protection considered necessary by organisations and individuals. This prompted the private security industry to develop new ways to train and educate private security personnel. In the early 1950s Paul Hansen, serving as the director of the Industrial Security Division of Reynolds Metals, met with five other private security professionals and established the beginnings of the national association of security directors. Their focus was to establish an organisation based from companies with specific expertise with guards, security fences, safes, locks and manual alarms. This organisation became known as the American Society for Industrial Security (ASIS) (today known as ASIS International).

ASIS International has been the leader in setting industry standards for training and certification programmes for private security personnel worldwide. Notably, ASIS has established one of the highest standards in security training and certification for private security professionals. Currently, ASIS certifications are the most difficult to achieve in the private security industry. Candidates must pass stringent comprehensive written examinations. However, in order to access the certification programmes any candidate must have a number of years of work experience in the private security industry.

Besides ASIS, a number of industry training and certification groups have developed since the establishment of ASIS, specifically to provide more in-depth standards for specific areas of the private security field (Maggio 2009: 13-22). In South Africa the University of South Africa may be singled out as the primary provider of tertiary level education in Security Risk Management.

Development of private security

Private security, which has grown into a large and international industry, can broadly be defined as an industry. Private security is also known as organisational security, corporate security, commercial security, asset protection, and security management (Smith & Brooks, 2013: 12). According to MacHovec (2006: vii), unlike law enforcement, security service providers are more involved in the personal lives of others and in the internal operations of companies, organisations, businesses and industry.

Without the provision of such security services, society and the world would be infinitely weaker and more susceptible (vulnerable) to predatory (opportunistic) crime and property loss. Such security service providers satisfy the needs of business and industry for protection wherever the local law enforcement is not sufficiently staffed or equipped to do so. In other words such need for security service providers arises where public policing agencies are ineffective in combating crime and carrying out their public mandate.

Providing the functions of an investigator are one of the activities of such security service providers (ie, in the ‘private sector’ as opposed to state security or public law enforcement) (MacHovec, 2006: 6). Many security officers are employed as guards, patrol officers and escorts protecting or safeguarding person/s or property against risks. Because security officers take their services to their clientele, the public are more likely to come into contact with a security officer than law enforcement officials (this is largely due to the absence of so-called ‘visible’ policing).

Shearing and Stenning’s statement (as cited in Berg, 2008: 1) that “Peel’s dream of a truly preventative police force” is being “substantially accomplished” through private security rather than through the state police thus holds true. This is evident in the fact that private security, while still retaining traditional private security tasks, are engaging more and more in law enforcement (policing) duties and activities, while also in some respects becoming increasingly involved in physical coercion, demonstrating greater symbolic and real powers (since much of what private security does remains largely unchallenged).

Community concern over the continued high levels of crime in South Africa has brought about an urgent need for changes in the field of investigation. The perceived inability of the authorities to cope with rising crime has forced companies and government departments to provide for the functions of an investigator (other than a public police officer/detective) to investigate security and crime threats, breaches, irregularities and criminality. The majority of medium to large companies in South Africa, including most government departments, have created their own investigation structures, staffed inter alia with experienced, professional and qualified investigators. This increase in the numbers of workplace investigators is allied to the general growth and increase in numbers of security personnel in the security service (Van Rooyen, 2008: 2; see also Minnaar and Ngoveni, 2004 and Minnaar, 2005 for more detail on the causes of this growth).

There has also been the concomitant growth of white-collar crimes such as fraud, insider dealings, cybercrime and copyright abuse and even business espionage, all of which have arisen in tandem with the shift to a post-industrial, information based-economy. These are often remarkably complex activities and they generally require specialised resources for the implementation of security and protection services as well as for their investigation – all services that may generally be unavailable to the public sector. Because financial stakes are high, it often makes sense to set up private security systems to protect investments (Smith and Natalier, 2005: 112).

In recent years, there has been an increase in the number of workplace investigators, due largely in turn to the growth in the number of security and crime threats, breaches, irregularities and criminality being reported by private business, industry and government service. In two cases the High Courts (of the Witwatersrand and Natal divisions) have in fact expressed their acceptance of the fact that private and workplace investigations occur [State vs Botha and others (1) 1995(2) SACR 598(W) and State vs. Dube 2000 (1) SACR 53 (N)]. This development created new opportunities for all investigators whether active in private, business, or government service and all indications are that the scope of their activities will increase (Van Rooyen, 2008: 4-5). Although this legal mandate created new opportunities for the security service to carry out an investigation function, both these cases did not recommend an amendment to the South African Police Service Act (powers to investigate), Criminal Procedures Act (powers of arrest, search and seizure), or the National Strategic Intelligence Act, (powers to collect and co-ordinate information) to legally empower private security officers to execute the investigative function as ethically and competently as a member of the South African Police Service.

Investigators from the security service sectors do both internal and external investigations for business, industrial and service companies. They do electronic sweeps to detect ‘bugged’ rooms, vehicles, or equipment to prevent theft of trade secrets (eg, a competitor’s agent working undercover as an employee within the company/business). They also protect executives from harassment, injury, kidnapping or terrorist attack. As undercover employees or consultants they can prevent fraud, theft, property damage or criminal acts by suppliers, employees or outsiders. Industrial security protects offices, factories, warehouses or prized possessions against damage or theft. Cybercrime investigators detect and prevent hackers from planting viruses or stealing credit card numbers or accessing a company’s information and operational databases (MacHovec, 2006: 8).

Security management studies at the University of South Africa (UNISA)

The vision of the programme: Security Management in the Department of Criminology & Security Science at the University of South Africa is broadly to “provide higher educational leadership to the private sector security services industry in Africa that will contribute to the empowerment of professional security practitioners.”

A further primary aim and objective being to assist in the further professionalisation of the private security industry in South Africa and Africa by providing tertiary qualifications with a focus on security management.

The qualifications offered by the Programme Security Management are the following:

1. Diploma in Security Management (NQF exit level 6 with some 3rd level security modules on NQF 7).

2. Advanced Diploma in Security Management exit level NQF7 (new in 2014).

3. Postgraduate Diploma in Security Management exit level NQF8 in 2015.

4. MTech in Security Management (MTSEC) with a full research dissertation (NQF 9).

5. DLitt et Phil (in Criminology with focus on Security Management) (NQF 10).

Currently these are the only tertiary (university level) qualifications in security management in South Africa, Africa and one of seven similar in the world approved by the Department of Higher Education and Training (DoHET), accredited with the Council of Higher Education (CHE), quality controlled in its Classification of Educational Subject Matter (CESM) category by the Higher Education Quality Committee (HEQC) and registered as such with the South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA). It is also the only such qualification in South Africa which conforms to the requirements of the Higher Education Qualifications Framework (HEQF).

All qualifications offered at UNISA are in the Open Distance Learning (ODL) mode of teaching which is not only cost effective but also convenient for working students to literally study part-time at their own pace spread over a number of years anywhere in the world, literally 'Learning Without Limits'. Technically such teaching is moving towards the provision of full online delivery.

The UNISA security management tertiary qualifications currently being offered by the University of South Africa (UNISA) were developed in response to a specific need for accredited tertiary academic qualifications for the private security industry in South Africa. Security officer training had its roots in two streams, namely the 1980 National Key Points Act (protection of strategic installations) and in-house security training, which was primarily of an operational nature.

In the early 1980s the then Institute for Criminological Sciences at UNISA initiated an informal (non-accredited) one-year certificate course in security management (modular non-degree programme) (Certificate in Security Management and the Advanced Certificate in Security Management).

In the early 1990s the broad mining industry approached and mandated the then TechnikonSA (TSA) to develop a specific tertiary accredited qualification (diploma & degree) for security managers. In response the TSA Faculty of Public Safety & Criminal Justice established the Programme Group: Security Management. The new three-year Diploma: Security Management was formally launched in 1995 with +150 students.

The early Security Management curriculum at the TSA followed the outline of the ASIS International 18 core security elements. These 18 elements are subfields in their own right but include the following:

1. Physical security.

2. Personnel security.

3. Information systems security.

4. Investigations.

5. Loss prevention.

6. Risk management.

7. Legal aspects.

8. Emergency and contingency planning.

9. Fire protection.

10. Crisis management.

11. Disaster management.

12. Counter-terrorism.

13. Competitive intelligence.

14. Executive protection.

15. Violence in the workplace.

16. Crime prevention.

17. Crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED).

18. Security architecture and engineering (ASIS International, 2009: 3-4).

In 1999, the fourth year of study for a BTech degree in Security Risk Management was formally rolled out by TSA. This qualification development continued and in 2003 the MTech in Security Management (masters level) programme was launched.

On the advice of the programme’s National Advisory Committee and in consultation with various sectors of the industry, a new first year module, namely: Security Technology, was developed and instituted in 2004.

With the merger in 2004 of the TSA and UNISA a review of all study offerings was undertaken and in line with the Department of Education’s (DoE) new Higher Education Qualifications Framework (HEQF) as per the 2004 & 2007 DoE policy framework documents, a revised and expanded Programme Qualification Mix (PQM) with a new curriculum compliant to a 360 credits (30 12-credit undergraduate modules – 10 at each year level of study of which 50% had to be security management focus = 15 modules) was developed.

The changes to the curriculum (starting in 2009 with the existing nine compulsory security modules) led to the revision and updating of these and the writing and development of SEVEN brand new security modules (1x1st level; 3x2nd level and 3x3rd level) and all had been rolled out by the start of the 2011 academic year.

In line with the International standard (ISO 31000-2009), and in consultation with the broad private security industry (PSI) via workshops with industry experts, these compulsory security modules in the diploma have been placed in five specialisation streams, namely:

• Security Principles & Practices (Management of Security).

• Security Risk Management.

• Security Risk Control Measures.

• Security Technology & Information Security.

• Corporate Investigation.

These qualifications’ curricula are designed for inculcating greater professionalism within the security industry in accordance with the business management approach. The main objective is to increase the professionalism of security practitioners in all sectors of the security industry. For example: city and metropolitan councils; transport services (rail, road, marine, aviation); public services (Telkom, Eskom, post office, hospitals); protection services (military, airforce, national intelligence, correctional services, government departments); financial and insurance institutions; industrial sector; mining sector; retail sectors (shops, shopping centres and hotels); private security contract companies, etc.

Accordingly, a qualification in Security Management and Security Risk Management will empower students to work in the following fields as an: investigating officer; operational officer; security supervisor/inspector; security site supervisor/manager; security operational manager; control room supervisors/managers; security risk managers, protection service managers and loss prevention. The business, law, labour, managerial knowledge and skills which the diploma and degree provide, enhances the possible employment of diplomandi and graduates in corporations and organisations, as well as in government departments.

In addition, on the advice of the industry, and in order to impart specific other specialised skills for security supervisors and managers inter alia language and literacy, computer skills, financial management, human resources, labour relations, and most crucially business management skills (with aspects of the law being covered in specific units in certain of the security modules), management modules were made compulsory while the other skills streams were accommodated in the two electives streams of which two elective modules to be taken each year, namely:

Stream 1: 1st-3rd level - Human Resources Management OR Labour Relations Management.

Stream 2: 1st level: Public Service Delivery OR Introduction to Management Accounting. 2nd level: Project Management OR Introduction to Crime Information Management. 3rd Level: Programme Management OR Crime Information Management.

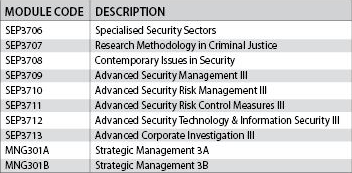

The specialisation streams in Security Management are carried through into the new Advanced Diploma with the addition of two new modules as well as a new research methodology module.

Advanced Diploma in Security Management (NQF7) 10 modules = 120 credits (see table)

Post Graduate Diploma In Security Management (planned rollout in 2016 approval by DoHET received in 2014 and accreditation by the CHE pending in 2015): FIVE (5) 24-credit modules NQF level 8 = 120 credits.

1. Applied Research Methodology In Security Science (incl. Research Article In Security Science) (SEP4801)

2. Advanced Security Technology & Information Security IV (SEP4802)

3. Advanced Security Risk Control Measures IV (SEP4803)

4. Advanced Security Risk Management IV (SEP4804)

5. Advanced Corporate Investigations IV (SEP4805)

6. Entry requirements: For the diploma an ordinary matric pass (Senior Certificate) (as opposed to ‘university exemption/endorsement’ matric pass which is necessary for accessing any degree) or NSC degree/diploma or equivalent qualification. If students are not in possession of these access criteria there are other routes to follow to enter tertiary studies at UNISA, ie, being 23 years and older or via the Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) process or with a number of years working experience in the industry. RPL provides a means to access the diploma dependent on such application to enter the formal RPL evaluation process.

RPL is the recognition by UNISA of any learning that occurred before the applicant decided to register for an academic qualification. In other words, the RPL programme enables a prospective student to gain recognition and credit for what they already know and can do (specific skills have already learnt). RPL makes it possible for you to earn credit/s towards a university academic qualification and thus to receive recognition at UNISA for skills and knowledge you already possess. Accordingly, RPL focuses on significant work-related experience.

You receive credit for what you have learned from your experience rather than from the experience itself. For example, if you have worked as a security officer for 10 years, you will have learned a vast number of skills: possibly supervising and managing security patrols; control room operations; corporate investigations; security risk analysis, working with security budgets, etc. These are the kinds of skills for which you could receive credit if you are wanting to be RPL-d for the Diploma in Security Management. Applicants to have at least a minimum of five (5) years of work-related experience in the subject/field (e.g. in the security environment) with at least three (3) years of experience at either supervisor or manager level.

Future plans

With the rollout in January 2014 of the new Advanced Diploma module study guides the academic staff of the Programme Security Management in the UNISA Department of Criminology and Security Science undertook the development and writing of the modules for the new planned Postgraduate Diploma in Security Management. This development work is due for completion in October 2015. Once that academic task is completed they will be turning their attention to the development of informal Short Learning Programmes (short courses), which will be offered in each semester. Currently only one such course is in use, the Security Risk Management one, which comprises of a weeklong series of face-to-face lectures which includes a practical site risk analysis exercise to a group of no more than 20 at a time.

The planned addition to this SLP will focus on extracting short courses from the current qualification offerings in security management.

1. Corporate Investigation.

2. Corruption Prevention in the workplace.

3. The application of Security Risk Control Measures.

4. Knowing how to design integrated security measures.

5. Technology and Security.

6. Practical information security for security officers.

These SLPs will be offered in each semester and while non-formal (ie, not accredited qualifications) students doing them can gain a certain number of credit exemptions for certain security module levels in the diploma, ie, on completion of such SLPs credits will be granted for security modules in the diploma so that a formal accredited qualification can be accessed. Emphasis in the SLPs to be on the case study approach with practical assignments to be completed. Hence, students wishing to enter formal studies will be able to fast track their studies by already starting off with some credits towards obtaining the formal and accredited Diploma in Security Management.

College of Economic & Management Sciences Short Learning Programmes In Management

Our sister college at UNISA the College of Economic & Management Sciences (CEMS) already offers (through the Centre For Business Management) a number of short courses in straight management studies (among our electives) for which a certain number of credit exemptions can also be obtained in order to access formal studies. Among the many offered by CEMS are the following which are assumed to be of practical value to security practitioners in the broad PSI:

1. Programme In Economics and Public Finance.

2. Financial Management (short course in Basic Financial Life Skills; short course in Basic Business Finance; course in Financial Management).

3. Programme in Business Management.

4. Programme in Business Continuity Management (introduction to enterprise-wide risk management; introduction to business continuity management).

5. Programme in Strategic Management and Corporate Governance.

6. Course in Strategic Management.

7. Course in Human Resource Management.

8. Course in Labour Relations Management.

9. Short course in Finance for Non-Financial Managers.

10. Course in Customer Relationship Management.

For more information, go to www.unisa.ac.za

Bibliography

ASIS. 2009. Private Security Officer Selection and Training. Retrieved February 2015, from https://www.asisonline.org/.../Private-Security-Officer-Selection-and-Training-Guideline.aspx

Berg, J. 2008. The private surveillance of public space: Evolving private security mentalities in South Africa. Unpublished Working Draft, June 2008.

MacHovec,F. 2006. Private security and security science: A scientific approach. Third edition. USA: Charles C Thomas.

Maggio, E.J. 2009. Private Security in the 21st Century. Concepts and Applications. Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

Minnaar, A. & Ngoveni, P. 2004. The relationship between the South African Police Service and the private security industry: Any role for outsourcing in the prevention of crime? Acta Criminologica: Southern African Journal of Criminology. 17(1): 42-65.

Minnaar, A. 2005. Private-public partnerships: Private security, crime prevention and policing in South Africa. Acta Criminologica: Southern African Journal of Criminology. 18(1): 85-114.

Smith, C.L. & Brooks, D.J. 2013. Security Science: The theory and practice of security. Elsievier: Butterworth-Heineman.

Smith, P. & Natalier, K. 2005. Understanding Criminal Justice: Socioligical Perspectives. London: Sage publications.

Van Rooyen, H.J.N. 2008. The Practitioners Guide to Forensic Investigations in South Africa: Pretoria. Henmar.

Decided cases

State vs Botha and others (1) 1995 (2) SACR 598 (W).

State vs Dube 2000 (1) SACR 53 (N)

© Technews Publishing (Pty) Ltd. | All Rights Reserved.